A chronic illness such as Cushing’s is likely to change your life in many ways. You may have had symptoms from excessive cortisol levels for quite a long time before Cushing’s was suspected and finally confirmed. Diagnosis is oftentimes followed by surgery and may also involve being on medication or receiving radiotherapy. Your illness is likely to have affected your appearance, your physical and mental abilities as well as your independence. You may not be able to work or may need to reduce your workload, causing financial problems.

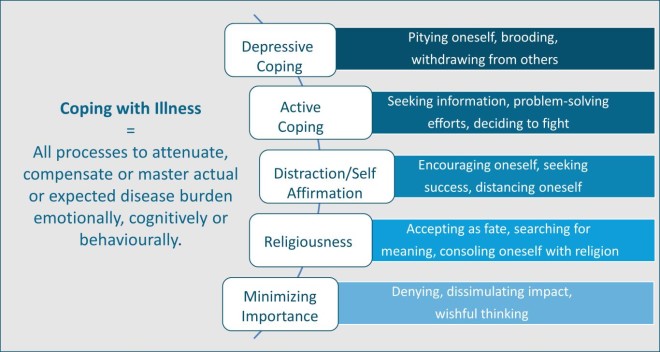

These tremendous changes are reason enough to cause stress, anxiety, frustration, anger and depression – mood states which additionally diminish your quality of living. This is where “coping” comes in. In psychology, coping is defined as a person’s own conscious effort to deal with difficult situations or life periods. The ways by which this is accomplished are called coping styles or coping strategies.

While we are growing up, we learn different coping strategies and some of them serve us well in problem solving throughout our life. These are called adaptive (constructive, active, or positive) coping strategies. “Active coping´´ involves mobilizing one’s own resources and employing strategies such as seeking information to better understand and deal with the illness as well as engaging in problem-solving efforts. Also, the so-called coping strategy “distraction/self-affirmation´´ is viewed as positive since this strategy comes along with behaviors where someone is able to distance and divert oneself from the disease for example, by having a massage or going out with friends. This strategy also involves encouraging oneself, for example by seeking success in what he or she is doing. Additionally, religiousness is viewed as one of the more constructive coping strategies since it can help people accept the disease and gain comfort in the belief in God.

On the other hand, there are also coping strategies which are negative for a person, such as avoidance, disengagement or denying the limitations set by an illness (also called “minimizing importance”), and “depressive coping´´ which is accompanied by pitying oneself or withdrawing from others. These negative coping styles affect our quality of life and well-being in unfavorable ways and are, therefore, called maladaptive coping styles. There are many different ways to categorize coping strategies. Figure 1 shows one classification we used in our study, which is summarized below.

Research on patients with diseases such as cancer, multiple sclerosis or diabetes mellitus has shown that patients with negative ways of coping have a worse quality of life and more depression that those who have more positive, adaptive coping strategies. Studies on patients with Cushing’s demonstrate that quality of life in patients oftentimes remains impaired years after successful treatment even though the disease itself may be well-controlled or in long term remission. In order to find out whether the coping strategies used by Cushing’s patients relate to quality of life, our group designed a study in which we sent out questionnaires on quality of life, depression, embitterment and coping strategies. These questionnaires were sent to more than 300 patients with Cushing’s disease treated at three major German university centers (Essen, Tübingen, Erlangen); 176 of these patients returned completed questionnaires and were included in the analysis.

Our patients who answered the questionnaires were on average almost seven years after their last pituitary surgery. Nevertheless, the overall degree of psychosocial impairment (poor quality of life, depression, anxiety, embitterment) remained high. At the time of the study, 21.8% of patients suffered from anxiety, 18.7% experienced an above-average feeling of embitterment, compared to the reference values of healthy people, and 13.1% suffered from depression. Our statistical analysis showed that patients who often used negative coping strategies such as depressive coping or minimizing importance had higher levels of depression, anxiety and embitterment and a poorer quality of life. Patient and illness related factors such as sex, age or hydrocortisone intake as a measure of secondary hypoadrenalism, had no such influence on their wellbeing.

In our eyes, this finding has a huge implication for patients with Cushing’s disease, because coping is a behavior that can be modified. Positive coping styles can be learned or reinforced. While there are currently no special programs to help Cushing patients cope with the particular aspects of their disease, most beneficial coping strategies are universally useful. Examples include learning to look at obstacles in a positive way, accepting the illness or building on social support and communication. Regardless of whether one has had Cushing’s disease or not, each of us is different in how we cope. Thus, each individual needs to identify coping strategies that work best for them. Counseling may help in determining what coping strategies a person currently uses and developing positive coping strategies, if needed. The results of our study indicate that the development of positive coping strategies can be a way to help yourself gain back quality of life despite the limitations Cushing’s may cause you.

Full text article: Siegel S, Milian M, Kleist B, Psaras T, Tsiogka M, Führer D, Koltowska-Häggström M, Honegger J, Müller O, Sure U, Menzel C, Buchfelder M, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I. Pituitary. 2016 Dec; 19(6):590-600.

By Ilonka Kreitschmann-Andermahr, Bernadette Kleist and Sonja Siegel, Spring, 2017

Editor´s Note: Prof. Dr. I. Kreitschmann-Andermahr is a neurologist with many years of experience in Cushing´s in the Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Essen (University of Duisburg-Essen) Essen, Germany.

1. Muthny FA (1989) Freiburger Fragebogen zur Krankheitsverarbeitung. Beltz Test GmbH, Weinheim

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.