As a neurologist and head of university outpatient departments in Germany, I see many patients with pituitary adenomas. In this capacity, I oftentimes hear the stories of patients with Cushing’s disease (CD; pituitary-induced Cushing’s) after years of bothersome symptoms and a long and winding road through the medical system before the correct diagnosis of Cushing’s is finally established and therapy can start.

Recent studies on Cushing’s syndrome (CS, meaning all forms of hypercortisolism, not just pituitary-induced) have found that it takes two years until 50% of the patients receive the correct diagnosis, which of course also means that the other 50% wait even longer to be diagnosed correctly.(1, 2) With the intent to gain some clues about why it takes so long until this rare disease is diagnosed, we systematically questioned 176 patients with CD about their experiences with the diagnostic process. We found that 3.8+/- 4.8 years elapsed before diagnosis during which time patients consulted 4.6 +/- 3.8 (range 1-30) physicians.

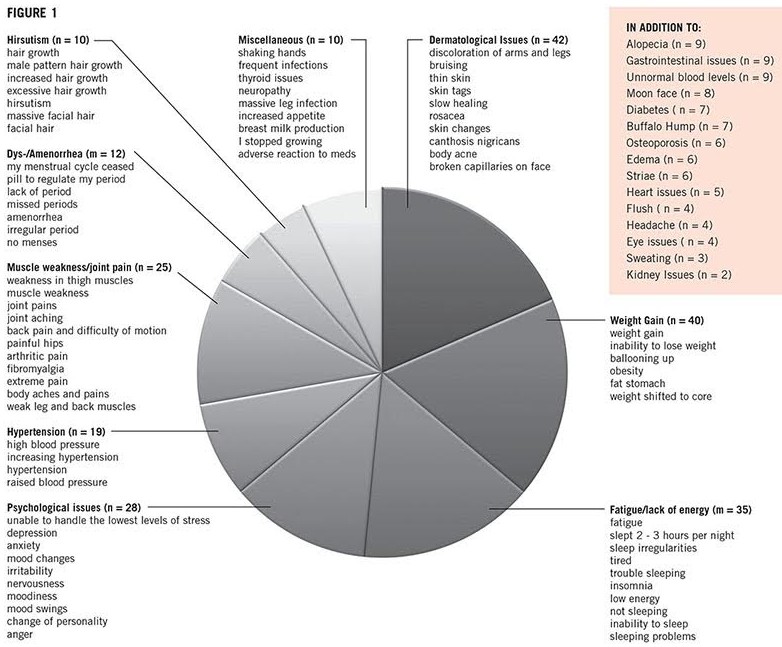

We also looked specifically at the symptoms patients reported and these answers gave us, as doctors, a lot to think about. Our patients experienced a large variety of symptoms which they retrospectively attributed to the onset of CD, and it was the very common symptom of weight gain which was noticed most uniformly. Patients also saw various medical specialists to gain relief from symptoms that are very common in the respective field of specialization, i.e. acne in dermatology, high blood pressure and diabetes in internal medicine and depression in neurology.

So, how can a doctor differentiate between an otherwise healthy patient with diabetes or acne versus a patient who is developing Cushing’s? Even if some symptoms, such as the so-called buffalo hump (the fat pad on the back of the neck), muscle weakness of the thigh muscles and easy bruising are more suggestive of the disease, there are many others such as weight gain, hypertension and diabetes that overlap with very common medical conditions in the general population. A small on-line survey recently conducted by the Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation (CSRF) illustrates this problem: You, the patients, were asked about what symptoms you reported to the first physician you thought could have considered a diagnosis of Cushing’s. A colleague in my research group clustered these symptoms and came up with Figure 1 (below).

Figure 1, which mirrors the results of our own study on the diagnostic process of CD, illustrates two points:

- Each of the symptom complexes — on its own — is not very specific for CS.

- Individual symptoms are worded in many different ways.

In the context of other more common diseases, Cushing’s is a rare condition. The core problem in medical decision-making is based on the fact that the probability of making or excluding a given diagnosis and the prevalence of a given condition are highly interrelated. In other words: the rarer a disease, the less likely it is that one test or one symptom will be able to lead to its identification, even if it is highly specific. More than 50 years ago, an American physician by the name of Charles A. Nugent suggested application of a mathematical rule, called Bayes Theorem, to the diagnostic process of CS (3). Bayes Theorem, set forth by the 18th century reverent Thomas Bayes, and very popular in modern evidence-based medicine, relates current to previous probabilities taking into account new pieces of evidence. The rule shows how the initially very low previous probability of a true diagnosis of a rare disease is influenced, when a new symptom or test result is added to the diagnostic process. In this context, Nugent demonstrated how the probability of an overweight patient being correctly diagnosed with CS increases considerably when the specific symptoms of muscle weakness and bruising or certain laboratory results such as low potassium are included in the statistical approach. For clinical practice, this means that uncovering characteristic combinations of symptoms (and test results) is extremely important. In order to do that, the doctor must:

- 1. Be aware of which symptoms go hand in hand in CS

- 2. Learn the art of spotting these symptoms

- 3. Learn to ask the right questions to bring forward information that the patient might not consider worth forwarding voluntarily

This requires clinical experience, knowledge about the disease and time. In this respect, patients’ help and feedback is extremely valuable in educating physicians on how to diagnose rare diseases earlier. More information on the diagnostic process can be used to train medical professionals and equally or more important, to train medical students. This is the reason why the CSRF and my research group at the University of Essen-Duisburg will soon be undertaking a more detailed study on the diagnostic process of Cushing’s. I hope that you will participate and share your experience.

Author: Dr. Ilonka Kreitschmann-Andermahr, Summer 2015

Editor’s Note: Prof. Dr. I. Kreitschmann-Andermahr, is a Neurologist with many years of experience in Cushing’s in the Department of Neurosurgery, University of Essen-Duisburg, Essen, Germany.

To read a CSRF Editors Note on Diagnosis, CLICK HERE

References:

- From first symptoms to final diagnosis of Cushing’s disease: experiences of 176 patients. Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Psaras T, Tsiogka M, Starz D, Kleist B, Siegel S, Milian M, Kohlmann J, Menzel C, Führer-Sakel D, Honegger J, Sure U, Müller O, Buchfelder M. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015 Mar;172(3):285-9. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0766. Epub 2014 Dec 10.

- The European Registry on Cushing’s syndrome: 2-year experience. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. Valassi E, Santos A, Yaneva M, Tóth M, Strasburger CJ, Chanson P, Wass JA, Chabre O, Pfeifer M, Feelders RA, Tsagarakis S, Trainer PJ, Franz H, Zopf K, Zacharieva S, Lamberts SW, Tabarin A, Webb SM; ERCUSYN Study Group. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011 Sep;165(3):383-92. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0272. Epub 2011 Jun 29.

- Probability theory in the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. Nugent CA, Warner HR, Dunn JT, Tyler FH. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1964 Jul;24:621-7.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.