On September 3, 2018, Dr. Ilonka Kreitschmann-Andermahr of the University of Duisburg-Essen and her team received news that the manuscript for their first-of-its-kind, patient-reported quality of life research had been accepted for publication in the International Journal of Endocrinology. The CSRF was happy to participate in this research, with former Director Karen Campbell contributing valuable effort in the initial stages to the design and language of the questionnaire used.

We are happy to see more research being done into the quality of life needs of patients experiencing Cushing’s, especially when patients’ direct input is a large part of the data being collected and analyzed. We look forward to participating in and reporting on much more of this type of research in the future! In fact, Dr. Kreitschmann-Andermahr was conducting a follow up study at the time of publication of this issue; you probably got an e-mail invitation to participate. Once the results of that are made available we will share them with membership.

Introduction

Cushing´s disease (CD) and Cushing´s syndrome (CS) are illnesses characterized by symptoms due to prolonged exposure to elevated cortisol levels, which are associated with increased morbidity and mortality from metabolic, musculo-sceletal, infectious, thrombotic, cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric complications [1, 2]. In CD, the cause of the hormone excess is an adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) secreting pituitary adenoma, which stimulates adrenal cortisol secretion [1]. In CS, the reason for hypercortisolism may be exogenous (i.e. prolonged glucocorticoid treatment) or endogenous, such as a benign or malignant cortisol-secreting tumor of the adrenal gland or paraneoplastic ACTH secretion [3, 4]. With an incidence of 2-3/ million, CS and CD are rare diseases [5-7].

Clinical signs and symptoms of Cushing’s include rapid weight gain, plethora, easy bruising, edema, proximal limb muscle fatigue, impaired glucose tolerance, mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, cognitive difficulties, osteoporosis and cardiovascular problems [1, 4, 8-10]. First line therapy is the surgical removal of the hormone-secreting tumor and, in cases of iatrogenic CS, lowering the dose of or discontinuing glucocorticoids if possible. If hypercortisolism cannot be normalized by these measures, radiotherapy, steroid-lowering medications or bilateral adrenalectomy may also be employed in patients with endogenous CS and CD [11, 12]. However, next to other therapeutic side effects, treatment of CS and CD often leads to hypocortisolism necessitating hydrocortisone replacement therapy and bearing the potential complication of life-threatening Addisonian crisis [13].

On the basis of the above, it becomes immediately clear that CS and CD are chronic diseases that may not be easily cured and have long-term effects on patients’ health, appearance, well-being and quality of life (QoL). Studies on patients with Cushing’s confirm that patients’ QoL can be impaired years after successful treatment even though the disease itself may be well-controlled or in long-term remission [9, 14-16].

In recent years, restoration of QoL in patients with chronic diseases has become an increasingly important treatment goal in clinical practice, resulting in the implementation of special support programs for many chronic diseases ranging from cancer and multiple sclerosis to diabetes mellitus [17-19]. It was, therefore, the aim of the present study to explore the disease burden and unmet support needs of patients with Cushing’s against the background of developing strategies for targeted patient support beyond medical interventions.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This cross-sectional patient-reported survey was conducted among adult (age ≥ 18 years) patients with CD who had undergone pituitary surgery for biochemically proven CD in two German neurosurgical university centers (Erlangen-Nuremberg and Duisburg-Essen) and patients with CD or CS who are members of the U.S. based Cushing’s Support and Research Foundation (CSRF) and who also had already received diagnosis and treatment of CD/CS. Inability to fill in the survey was the only exclusion criterion.

Survey/Questionnaire description

A patient-reported outcome survey (PRO-survey) was developed to assess information about: 1) current burden of Cushing-related symptoms, 2) time points when support was needed the most, 3) factors that have helped the patients the most in coping with the disease, 4) disease-specific support needs, interest in a support program and topics of interest. These questions were compiled based on the results of former research by our group [10] and the current state of research on QoL and coping in patients with CD and CS [9, 14-16]. A neurologist (IKA), a neurosurgeon (MB), a psychologist (SoS) and, for the U.S. version of the questionnaire, one of the former directors (KC) of the CSRF developed the survey.

The survey comprised 14 questions to be answered based on given response options or as a free-text. The interest of the participants in a support program was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, using the statements: not at all, a little, moderate, a lot and absolutely. The statements were coded from 1 (not at all) to 5 (absolutely) for statistical analyses. The questionnaire was developed in German, and for the U.S. participants was translated into English by a state-certified translator (IKA) and by native English speaking neurosurgeon in training (VK) and checked by KC to ensure comprehension of the translated questions.

For easier handling, the questionnaire was then programmed as an online-based survey that could be filled in by the U.S. patients via an activation link for a homepage sent by e-mail via the CSRF. The homepage was operated by the University Hospital Essen (Germany) and was hosted on a secure server of the hospital. The German patients received the paper-based version by mail.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki [20, 21]. All patients gave informed consent and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Results

84 U.S. and 71 German patients answered the questionnaire. There was no difference between groups with regard to sex and age (p>0.05, Table 1).

|

Table 1: Characteristics of the study population for both groups. Data are presented as frequency (n) and valid percent (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

|||

|

Variable |

U.S. (n=84) |

Germany (n=71) |

p-Value |

|

Sex Female Male |

77 (91.7) 7 (8.3) |

59 (83.1) 12 (16.9) |

0.141 |

|

Age (years) |

50.1 ± 13.73 |

48.8 ± 13.64 |

0.555 |

|

Reason for hypercortisolism Pituitary adenoma Adrenal tumor Others† |

56 (66.7) 21 (25.0) 7 (8.3) |

71 (100.0) – – |

|

|

aFisher´s exact test. †Other reasons are: Pursuing ectopic or pituitary (n=1), bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (n=1), ectopic ACTH syndrome (n=2), steroid treatment (n=3). |

|||

Disease burden

In response to the question “Which aspects of your Cushing´s condition bother/bothered you the most?” which assessed current or past disease burden, patients reported a variety of aspects which could be clustered into four major symptom groups (answers provided in a free-text field): 1) Symptoms related to cortisol overproduction (overweight, moon face, skin problems, sweating, muscle weakness), 2) reduced performance (tiredness, fatigue), 3) psychological impairment (including depression, anxiety, fears and cognitive decline) and 4) length of diagnostic process (comments regarding the time it took until the correct diagnosis was made). Table 2 shows the frequencies of answers for each cluster, together with a selection of the participants´ answers in their own words. Comments about the length of the diagnostic process were only provided by U.S. patients.

|

Table 2: Answers of the patients in regard to the question “Which aspects of your Cushing condition bother/bothered you the most?´´ Answers were clusterd and counted. Data are presented as frequency (n) and valid percent (%). |

||

|

Variable |

U.S. (n=84) |

Germany (n=65) |

|

Common symptoms related to cortisol overproduction Moon face, buffalo hump, red cheeks, bruises that wouldn´t heal, transparent skin, inability to lose weight, acne, fat belly, high blood pressure, heart racing, cardio -pulmonary effects, tachycardia, hair growth, dizziness, body pain, swelling of body/limbs, sweating |

71 (84.5) |

34 (52.3) |

|

Reduced performance Muscle weakness, muscle loss, morning insomnia, to weak and in pain to exercise, fatigue, tired all the time, low energy |

39 (46.4) |

24 (36.9) |

|

Psychological impairment Being depressed, depression, anxiety, panic attacks, nervous, scared, I felt like I was going crazy, tantrums, sexual dysfunction, feeling crummy, cognitive changes, feeling sick, neg. effects on self-confidence, having to go it a alone, angry for no reason, confused in large crowds/noisy places, felt like I was on psychotropic drugs and slipping between dimensions, was not myself and did not know why Being cyclical, unable to predict what would be next, feeling something was very wrong, worry about residual effects on my brain Very poor concentration, foggy brain, memory and attention issues, permanent deficits in memory, brain always racing, forgetfulness, brain didn´t work properly, memory loss |

51 (60.8) |

43 (66.2) |

|

Diagnostic process Fighting for diagnosis; the doctors inability to link all of these symptoms; was asked if I needed counseling for my obsession with my health; how long it took for a diagnosis; I suffered for years at the hand of doctors; MDs not listening and saying stupid things like I was stressed out |

8 (9.5) |

– |

Coping strategies

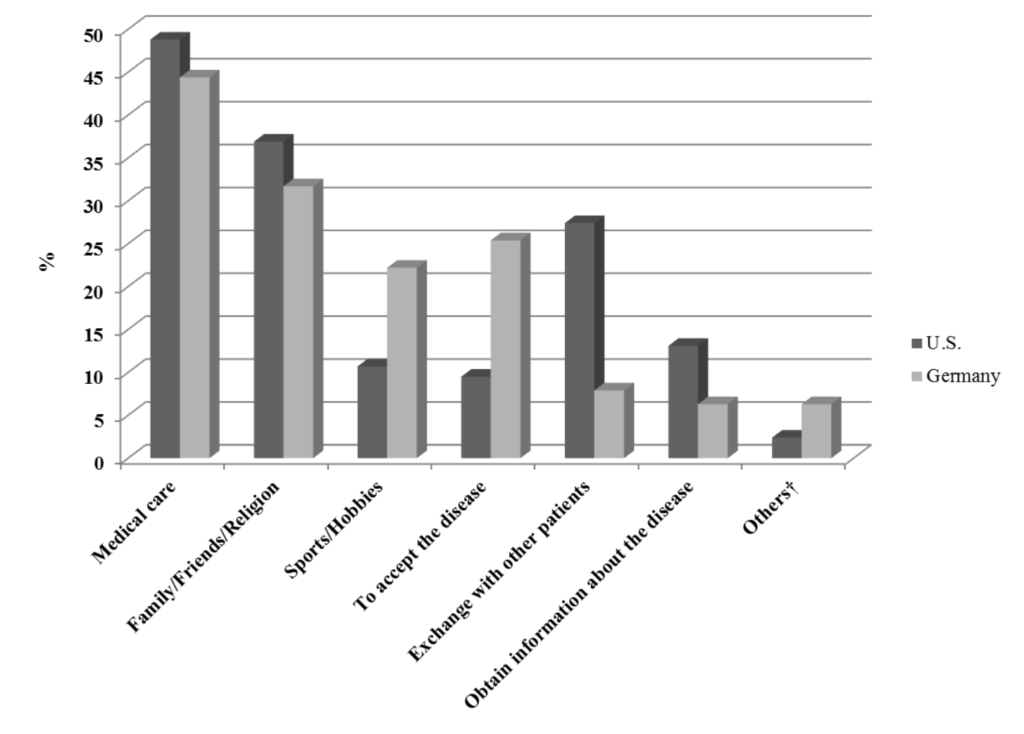

48.8% of patients from the U.S. and 44.4% of the German patients stated that good medical care and competent, skilled doctors were of major help in coping with Cushing’s, followed by the support of family/ friends and religion (U.S.: 36.9% vs. Germany: 31.7%). Sports and hobbies (U.S.: 10.7% vs. Germany: 22.2%) as well as accepting the disease (U.S.: 9.5% vs. Germany: 25.4%) were used more often by German patients as coping strategies to deal with the disease, whereas the exchange with other patients (U.S.: 27.4% vs. Germany: 7.9%) and to obtain information about the disease (U.S.:13.1% vs. Germany: 6.3%) was more important to the U.S. patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Factors that helped the patients the most in coping with the illness.

Support needs

Support was needed to a greater extent before therapy by the U.S patients (63.1%) than by the German patients (45.1%) with p=0.035. 12.7% of the German patients even stated not to have wanted further support at any time of their illness, compared to only 2.4% of the U.S. patients (p=0.024; Table 3). On the other hand, U.S. patients were more interested in support groups, in courses on illness coping, in seminars and workshops and educational offers for the family than the German patients (all p<0.05), who stated to prefer brochures (45.1% vs 20.2%, p=0.001; Table 3).

|

Table 3: Support needs of the patients. Data are presented as frequency and valid percent (%). |

|||

|

Variable |

U.S. (n=84) |

Germany (n=71) |

p-Value |

|

Stages at the course of the disease patients wished for more support (multiple answers possible) |

|||

|

Before therapy In the weeks directly after therapy Within the first year after start of therapy Never |

53 (63.1) 36 (42.9) 38 (45.2) 2 (2.4) |

32 (45.1) 26 (36.6) 30 (42.3) 9 (12.7) |

0.035 0.511 0.747 0.024 – |

|

Current interest in different kinds of supportive offers (multiple answers possible) |

|||

|

In person support group Webinar/Online forum Lectures Courses on coping with the illness Seminars or Workshops Leaflets/brochures Educational offers for the family Others†† No interest |

43 (51.2) 45 (53.6) 29 (34.5) 41 (48.8) 31 (36.9) 17 (20.2) 29 (34.5) 12 (14.3) 5 (6.0) |

24 (33.8) 28 (39.4) 31 (43.7) 19 (26.8) 13 (18.6) 32 (45.1) 8 (11.4) 7 (10.1) 9 (12.9) |

0.035 0.106 0.253 0.008 0.019 0.001 0.001 0.472 0.166 |

The general interest (assessed by Likert scale) in a specific support program for patients with Cushing´s was higher in U.S. patients (3.8 ± 1.10) than in German patients (3.1 ± 1.26) with p=0.001 (Mann-Whitney-U test). 28 (33.3%) of the U.S. patients but only 11 (15.9%) of the German patients stated a very strong interest and 21 (25.0%) of the U.S patients and 15 (21.7%) of the German patients stated a considerable interest in such a program. Nine (13.0%) German and 2 (2.4%) U.S. patients expressed no interest in a support program.

In regard to specific topics that should be covered by a support program more U.S. patients than German patients wished to communicate with other patients (75.0% vs. 52.9%, p=0.006) and to learn more about stress management (60.7% vs. 33.8%, p=0.001; Table 4). 89.3% of U.S. patients would attend internet-based programs compared to 75.4% of German patients (p=0.040). There were no differences between groups for the preferred duration of and the willingness to pay for such a program, but U.S. patients would be willing to travel longer distances to attend a support meeting (p=0.027; Table 4).

|

Table 4: Questions concerning educational and support programs. Data are presented as frequency and valid. percent (%) or as mean ± standard deviation. |

|||

|

Variable |

U.S. |

Germany |

p-Value |

|

Topics for educational and support programs the patients are interested in (multiple answers possible) Communicating with other people Relaxation Nutritional advice Stress management Exercise Health Care Bureaucracy/Financial Issues |

(N=84) 63 (75.0) 37 (44.0) 43 (51.2) 51 (60.7) 44 (52.4) 30 (35.7) |

(N=68) 36 (52.9) 25 (36.8) 31 (45.6) 23 (33.8) 31 (45.6) 23 (33.8) |

0.006 0.409 0.518 0.001 0.420 0.865 |

|

Coping with daily hassles |

31 (36.9) |

21 (30.9) |

0.493 |

|

Others |

20 (23.8) |

16 (24.2) |

1.000 |

|

Type of program the patients are interested in (multiple answers possible) Internet-based program In person seminars – weekend meetings In person seminars – meetings during the week |

(N=84) 75 (89.3) 39 (46.4) 30 (35.7) |

(N=61) 46 (75.4) 21 (34.4) 13 (21.3) |

0.040 0.173 0.068 |

|

Duration of the program Several hours Entire day Entire weekend Flexible timing (available through internet courses only) |

(N=84) 36 (42.9) 11 (13.1) 2 (2.4) 35 (41.7) |

(N=60) 22 (36.7) 10 (16.7) 2 (3.3) 26 (43.3) |

0.494 0.634 1.000a 0.866 |

|

How far would the patients travel to attend such an in person seminar? Milesb |

(N=76) 168.0 ± 468.01 |

(N=48) 46.9 ± 49.54 |

0.027 |

|

How many patients would be willing to pay for a support program? Yes No |

(N=84) 51 (60.7) 33 (39.3) |

(N=59) 31 (52.5) 28 (47.5) |

0.391 |

|

How much would the patients be willing to pay for a support program? Dollar Euro |

(N=48) 150.9 ± 243.35 137.0 ± 220.81 |

(N=30) 100.7 ± 196.31 91.3 ± 178.13 |

0.501 0.501 |

|

a Fisher´s exact test. b1 mile=1.609 kilometers |

|||

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first patient-reported survey which demonstrates the need for additional support apart from medical interventions in patients with CD or CS, although the negative long-term impact of these illnesses on health-related QoL has been confirmed in many studies [22-27]. Patients in both Germany and the USA who completed our survey reported a wide spectrum of past or present Cushing-related symptoms, psychological impairment as well as reduced physical and mental performance. In line with the high subjective illness distress, the vast majority of the participants (97% in the USA, 87% in Germany) stated that they wanted additional support at any time during the disease, most often after diagnosis and during the first year of treatment. Many of them were willing to pay for such additional support.

This snapshot is in accordance with themes discussed in focus groups of pituitary adenoma patients and conducted by a Dutch research group, where mood problems, negative illness perceptions, issues of physical, cognitive and sexual functioning were among the most prominent complaints of patients with [28] CD. Based on the feedback provided by their focus group participants, the research group developed and validated a questionnaire for pituitary patients, which aims to assess to what extent patients are bothered by consequences of the disease as well as their needs for support [29]. However, results on the practicability and usefulness of this questionnaire and the consequences drawn thereof in clinical practice are yet to be awaited.

The Dutch researchers’ focus group results and the feedback given by our surveyed patients reflect unmet support needs despite receiving medical care in modern western healthcare environments. Patients with CD and CS carry the burden of their illness that often develops insidiously and may remain undiagnosed for a long time, and causes physical disfigurement and severe co-morbidities. The illness may not necessarily become controlled after surgical and/or medical intervention. Moreover, by the nature of hypercortisolism in active and hypocortisolism in treated disease, CD and CS are prone to be accompanied by mental symptoms such as depression and anxiety [30, 31]. Such a course of illness requires constant adaptation and possibly changes of patients’ healthcare management to control symptoms, which can cause patients to experience stress and uncertainty [32].

In some respects, modern health care systems have already acknowledged the additional support needs of chronically ill patients. The insight, indicating that a model of care, where the patient is seen as the recipient and the physician as the giver of medical care, does not suit the needs and reality for most patients with chronic illnesses. This has led to the development of new models of care in which patients move from a passive role as healthcare recipients towards an active role as an equally important partners in the management of their illness. The Chronic Care Model (CCM) developed by Wagner et al. in 2001 [33] is such a model, according to which high-quality chronic illness care involves collaborative, productive interactions between active and well-informed patients and multidisciplinary teams of healthcare providers on the topics of illness assessment, optimization of therapy and follow-up as well as self-management support [34]. It has been estimated that 70–80% of people living with chronic illness could reduce their illness burden and costs by appropriate self-management [35]. For such reasons, the improvement of patients’ abilities in the self-management of their illness is a major component of patient support programs. Such programs have already been implemented for patients with cancer, multiple sclerosis, diabetes mellitus, chronic back pain and other diseases [18, 19, 36-42]. Many of these programs are well received by the respective patient populations and have demonstrated a high degree of effectiveness in terms of better health outcomes, QoL and functional status [43-45]. A recent definition of health has even acknowledged the importance of self-management by defining health as ‘the ability to adapt and self-manage in the face of social, physical, and emotional challenges’ [46].

The multitude of reported positive effects, ranging from improved clinical and psychosocial outcome over better adherence and self-management to decreased health care costs, encourages the development of specific support programs for CD/CS [17, 47, 48]. However, in the case of CD and CS the development of special programs devoted solely to this patient group are likely to be cost-intensive and, due to the rareness of the disease, beneficial to only very few patients. Yet, despite the unique features of their illness, patients with Cushing’s do not differ in all respects from other patients with chronic conditions such as heart disease, multiple sclerosis or diabetes. Common challenges associated with the management of such conditions include dealing with symptoms and disability, managing complex medication regimes, having to make lifestyle changes, maintaining a proper diet and exercise, adjusting to psychological and social demands and to engage in effective interaction with their health care professionals. A study by our group has shown that negative coping strategies are a major determinant of poor QoL, depression and embitterment in patients with CD [10]. Since many techniques like learning adaptive coping strategies, rules for healthy nutrition or basic exercises are universally useful, the adaption of already existing programs from other diseases might be a sensible first step for the establishment of self-management programs for patients with Cushing’s.

Such an effort has already been made for patients with pituitary disease in general, by a Dutch research group, who implemented and evaluated a Patient and Partner Education Programme for Pituitary Disease (PPEP-Pituitary) (33). They found positive effects of this program in patients and partners and concluded that future research should focus on the refinement and implementation of such a self-management program into clinical practice.

Our results suggest that such a program should focus on the time before and first year after treatment, which due to the sudden cortisol deprivation is severely stressful for the patient. Topics worth covering might be communication, nutritional advice and exercise, since these are the topics most frequently requested in both countries. Stress management seems to be of interest especially to U.S. patients. Also, the setting should be adapted to cultural preferences. In the USA, in-person support groups are highly desired with patients willing to travel considerable distances and pay for such programs, while German patients seem to prefer written information in leaflets or brochures. Patients in both countries express interest in web-based forms of support.

Last but not least, our results underline the importance of patient support groups that are already in place. Already a quarter of the U.S. patients report, that the exchange with other patients was most helpful to them. Nevertheless, 50% express a wish for more patient support groups. It can be speculated, that some patients might not know about already existing groups. Oftentimes it might already improve a patient’s wellbeing to ensure that he has access to all the existing support like support groups or information material.

One limitation of the present study is that the use of patient response tools such as a PRO survey may have introduced a bias as it can be speculated that patients with a higher disease burden are more likely to participate in a survey querying disease symptoms and need for support. Nevertheless, the results must be understood as a call to identify, implement and evaluate valid support programs with an emphasis of self-management for patients with Cushing’s and other endocrine diseases, preferably in a multi-center setting. Culture-specific support needs should also be taken into account.

Conclusion

Patients with Cushing’s in the USA and Germany need competent physicians and long-term medical care in dealing with the effects of CD/CS, but also request additional support besides medical interventions, while the interest in specific topics addressed in support programs differs somewhat between patients of both countries. The latter implies that not only disease-specific but also culture-specific training programs would need to be considered to satisfy the needs of patients in different countries.

References

[1] A. Buliman, L. G. Tataranu, D. L. Paun, A. Mirica, and C. Dumitrache, “Cushing’s disease: a multidisciplinary overview of the clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment,” J Med Life, vol. 9, pp. 12-18, Jan-Mar 2016.

[2] F. Castinetti, I. Morange, B. Conte-Devolx, and T. Brue, “Cushing’s disease,” Orphanet J Rare Dis, vol. 7, p. 41, 2012.

[3] J. W. Findling and H. Raff, “DIAGNOSIS OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Differentiation of pathologic/neoplastic hypercortisolism (Cushing’s syndrome) from physiologic/non-neoplastic hypercortisolism (formerly known as pseudo-Cushing’s syndrome),” Eur J Endocrinol, vol. 176, pp. R205-r216, May 2017.

[4] J. K. Prague, S. May, and B. C. Whitelaw, “Cushing’s syndrome,” Bmj, vol. 346, p. f945, 2013.

[5] J. Lindholm, S. Juul, J. O. Jorgensen, J. Astrup, P. Bjerre, U. Feldt-Rasmussen, et al., “Incidence and late prognosis of cushing’s syndrome: a population-based study,” J Clin Endocrinol Metab, vol. 86, pp. 117-23, Jan 2001.

[6] L. K. Nieman, B. M. Biller, J. W. Findling, J. Newell-Price, M. O. Savage, P. M. Stewart, et al., “The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.,” J Clin Endocrinol Metab, vol. 93, pp. 1526-40, 2008.

[7] C. Steffensen, A. M. Bak, K. Z. Rubeck, and J. O. Jorgensen, “Epidemiology of Cushing’s syndrome,” Neuroendocrinology, vol. 92 Suppl 1, pp. 1-5, 2010.

[8] A. Bratek, A. Kozmin-Burzynska, E. Gorniak, and K. Krysta, “Psychiatric disorders associated with Cushing’s syndrome,” Psychiatr Danub, vol. 27 Suppl 1, pp. S339-43, Sep 2015.

[9] R. A. Feelders, S. J. Pulgar, A. Kempel, and A. M. Pereira, “The burden of Cushing’s disease: clinical and health-related quality of life aspects,” Eur J Endocrinol, vol. 167, pp. 311-26, Sep 2012.

[10] S. Siegel, M. Milian, B. Kleist, T. Psaras, M. Tsiogka, D. Fuhrer, et al., “Coping strategies have a strong impact on quality of life, depression, and embitterment in patients with Cushing’s disease,” Pituitary, Sep 2 2016.

[11] G. Arnaldi and M. Boscaro, “New treatment guidelines on Cushing’s disease,” F1000 Med Rep, vol. 1, Aug 17 2009.

[12] B. M. Biller, A. B. Grossman, P. M. Stewart, S. Melmed, X. Bertagna, J. Bertherat, et al., “Treatment of adrenocorticotropin-dependent Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement,” J Clin Endocrinol Metab, vol. 93, pp. 2454-62, Jul 2008.

[13] M. Quinkler, “[Addison’s disease],” Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed, vol. 107, pp. 454-9, Sep 2012.

[14] X. Badia, E. Valassi, M. Roset, and S. M. Webb, “Disease-specific quality of life evaluation and its determinants in Cushing’s syndrome: what have we learnt?,” Pituitary, vol. 17, pp. 187-95, Apr 2014.

[15] A. H. Heald, S. Ghosh, S. Bray, C. Gibson, S. G. Anderson, H. Buckler, et al., “Long-term negative impact on quality of life in patients with successfully treated Cushing’s disease,” Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), vol. 61, pp. 458-65, Oct 2004.

[16] J. R. Lindsay, T. Nansel, S. Baid, J. Gumowski, and L. K. Nieman, “Long-term impaired quality of life in Cushing’s syndrome despite initial improvement after surgical remission,” J Clin Endocrinol Metab, vol. 91, pp. 447-53, Feb 2006.

[17] G. Bouma, J. M. Admiraal, E. G. de Vries, C. P. Schroder, A. M. Walenkamp, and A. K. Reyners, “Internet-based support programs to alleviate psychosocial and physical symptoms in cancer patients: a literature analysis,” Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, vol. 95, pp. 26-37, Jul 2015.

[18] R. E. Glasgow, M. Barrera, Jr., H. G. McKay, and S. M. Boles, “Social support, self-management, and quality of life among participants in an internet-based diabetes support program: a multi-dimensional investigation,” Cyberpsychol Behav, vol. 2, pp. 271-81, 1999.

[19] M. Rijken, N. Bekkema, P. Boeckxstaens, F. G. Schellevis, J. M. De Maeseneer, and P. P. Groenewegen, “Chronic Disease Management Programmes: an adequate response to patients’ needs?,” Health Expect, vol. 17, pp. 608-21, Oct 2014.

[20] F. D. A. Departement of Health and Human Services, “International Conference on Harmonisation; Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guideline,” Federal Register1997.

[21] World Medical Association, “World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects,” Jama, vol. 310, pp. 2191-4, Nov 27 2013.

[22] V. Papoian, B. M. Biller, S. M. Webb, K. K. Campbell, R. A. Hodin, and R. Phitayakorn, “PATIENTS’ PERCEPTION ON CLINICAL OUTCOME AND QUALITY OF LIFE AFTER A DIAGNOSIS OF CUSHING SYNDROME,” Endocr Pract, vol. 22, pp. 51-67, Jan 2016.

[23] J. Tiemensma, A. A. Kaptein, A. M. Pereira, J. W. Smit, J. A. Romijn, and N. R. Biermasz, “Negative illness perceptions are associated with impaired quality of life in patients after long-term remission of Cushing’s syndrome,” Eur J Endocrinol, vol. 165, pp. 527-35, Oct 2011.

[24] E. Valassi, R. Feelders, D. Maiter, P. Chanson, M. Yaneva, M. Reincke, et al., “Worse Health-Related Quality of Life at long-term follow-up in patients with Cushing’s disease than patients with cortisol producing adenoma. Data from the ERCUSYN,” Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), Mar 24 2018.

[25] M. O. van Aken, A. M. Pereira, N. R. Biermasz, S. W. van Thiel, H. C. Hoftijzer, J. W. Smit, et al., “Quality of life in patients after long-term biochemical cure of Cushing’s disease,” J Clin Endocrinol Metab, vol. 90, pp. 3279-86, Jun 2005.

[26] M. A. Wagenmakers, R. T. Netea-Maier, J. B. Prins, T. Dekkers, M. den Heijer, and A. R. Hermus, “Impaired quality of life in patients in long-term remission of Cushing’s syndrome of both adrenal and pituitary origin: a remaining effect of long-standing hypercortisolism?,” Eur J Endocrinol, vol. 167, pp. 687-95, Nov 2012.

[27] S. M. Webb, A. Santos, E. Resmini, M. A. Martinez-Momblan, L. Martel, and E. Valassi, “Quality of Life in Cushing’s disease: A long term issue?,” Ann Endocrinol (Paris), Apr 3 2018.

[28] C. D. Andela, N. D. Niemeijer, M. Scharloo, J. Tiemensma, S. Kanagasabapathy, A. M. Pereira, et al., “Towards a better quality of life (QoL) for patients with pituitary diseases: results from a focus group study exploring QoL,” Pituitary, vol. 18, pp. 86-100, Feb 2015.

[29] C. D. Andela, M. Scharloo, S. Ramondt, J. Tiemensma, O. Husson, S. Llahana, et al., “The development and validation of the Leiden Bother and Needs Questionnaire for patients with pituitary disease: the LBNQ-Pituitary,” Pituitary, vol. 19, pp. 293-302, Jun 2016.

[30] R. Pivonello, M. C. De Martino, M. De Leo, C. Simeoli, and A. Colao, “Cushing’s disease: the burden of illness,” Endocrine, vol. 56, pp. 10-18, Apr 2017.

[31] R. Pivonello, C. Simeoli, M. C. De Martino, A. Cozzolino, M. De Leo, D. Iacuaniello, et al., “Neuropsychiatric disorders in Cushing’s syndrome,” Front Neurosci, vol. 9, p. 129, 2015.

[32] L. van Houtum, M. Rijken, M. Heijmans, and P. Groenewegen, “Self-management support needs of patients with chronic illness: do needs for support differ according to the course of illness?,” Patient Educ Couns, vol. 93, pp. 626-32, Dec 2013.

[33] E. H. Wagner, B. T. Austin, C. Davis, M. Hindmarsh, J. Schaefer, and A. Bonomi, “Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action,” Health Aff (Millwood), vol. 20, pp. 64-78, Nov-Dec 2001.

[34] E. H. Wagner, R. E. Glasgow, C. Davis, A. E. Bonomi, L. Provost, D. McCulloch, et al., “Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach,” Jt Comm J Qual Improv, vol. 27, pp. 63-80, Feb 2001.

[35] R. Gallagher, J. Donoghue, L. Chenoweth, and J. Stein-Parbury, “Self-management in older patients with chronic illness,” Int J Nurs Pract, vol. 14, pp. 373-82, Oct 2008.

[36] P. Hampel and L. Tlach, “Cognitive-behavioral management training of depressive symptoms among inpatient orthopedic patients with chronic low back pain and depressive symptoms: A 2-year longitudinal study,” J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil, vol. 28, pp. 49-60, 2015.

[37] T. Kohlmann, C. Wang, J. Lipinski, N. Hadker, E. Caffrey, M. Epstein, et al., “The impact of a patient support program for multiple sclerosis on patient satisfaction and subjective health status,” J Neurosci Nurs, vol. 45, pp. E3-14, Jun 2013.

[38] S. Kopke, T. Richter, J. Kasper, I. Muhlhauser, P. Flachenecker, and C. Heesen, “Implementation of a patient education program on multiple sclerosis relapse management,” Patient Educ Couns, vol. 86, pp. 91-7, Jan 2012.

[39] R. Maguire, G. Kotronoulas, M. Simpson, and C. Paterson, “A systematic review of the supportive care needs of women living with and beyond cervical cancer,” Gynecol Oncol, vol. 136, pp. 478-90, Mar 2015.

[40] H. G. McKay, D. King, E. G. Eakin, J. R. Seeley, and R. E. Glasgow, “The diabetes network internet-based physical activity intervention: a randomized pilot study,” Diabetes Care, vol. 24, pp. 1328-34, Aug 2001.

[41] M. Monticone, E. Ambrosini, B. Rocca, S. Magni, F. Brivio, and S. Ferrante, “A multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme improves disability, kinesiophobia and walking ability in subjects with chronic low back pain: results of a randomised controlled pilot study,” Eur Spine J, vol. 23, pp. 2105-13, Oct 2014.

[42] C. Paterson, A. Robertson, A. Smith, and G. Nabi, “Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: A systematic review,” Eur J Oncol Nurs, vol. 19, pp. 405-18, Aug 2015.

[43] M. G. Ory, S. Ahn, L. Jiang, M. L. Smith, P. L. Ritter, N. Whitelaw, et al., “Successes of a national study of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program: meeting the triple aim of health care reform,” Med Care, vol. 51, pp. 992-8, Nov 2013.

[44] W. van der Vlegel-Brouwer, “Integrated healthcare for chronically ill. Reflections on the gap between science and practice and how to bridge the gap,” Int J Integr Care, vol. 13, p. e019, Apr 2013.

[45] T. Vandiver, T. Anderson, B. Boston, C. Bowers, and N. Hall, “Community-Based Home Health Programs and Chronic Disease: Synthesis of the Literature,” Prof Case Manag, vol. 23, pp. 25-31, Jan/Feb 2018.

[46] M. Huber, J. A. Knottnerus, L. Green, H. van der Horst, A. R. Jadad, D. Kromhout, et al., “How should we define health?,” Bmj, vol. 343, p. d4163, Jul 26 2011.

[47] A. Ganguli, J. Clewell, and A. C. Shillington, “The impact of patient support programs on adherence, clinical, humanistic, and economic patient outcomes: a targeted systematic review,” Patient Prefer Adherence, vol. 10, pp. 711-25, 2016.

[48] U. Stenberg, M. Haaland-Overby, K. Fredriksen, K. F. Westermann, and T. Kvisvik, “A scoping review of the literature on benefits and challenges of participating in patient education programs aimed at promoting self-management for people living with chronic illness,” Patient Educ Couns, vol. 99, pp. 1759-1771, Nov 2016.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.